What the Welfare Fraud Reveals About Laissez-Faire: A Mandevillian Response to the Wall Street Journal

A recent Wall Street Journal opinion piece, “Minnesota’s Fraud Problem Isn’t Immigrants”, examines Minnesota’s welfare fraud scandal and warns against reducing it to a narrative about bad actors or suspect communities. Instead, it emphasizes failures of oversight and political accountability. That caution is important, but incomplete.

Turning the scandal into a familiar true-crime story with villains and verdicts may feel satisfying, yet it obscures more than it elucidates. And when we stop there, we leave ourselves in a state of cognitive dissonance, avoiding a harder truth Americans are rarely asked to face: our society is not organized around virtue; it is organized around self-interest.

American society builds its prosperity on foundations it probably prefers not to name—foundations first articulated by Bernard Mandeville, who elevated self-interest from vice into a governing principle. This is not a fringe idea. It is the foundation of modern political economy.

Laissez-faire economics attacks the belief that luxury—by corrupting a people and wasting its resources—is economically dangerous. On the contrary, Mandeville argued that luxury is not only inseparable from great states, but necessary to make them great, even as modern laissez-faire publicly denies this moral paradox at the heart of its prosperity.

The problem arises when the consequences of individualism surface and society declines to examine the assumptions about human nature and knowledge that underwrite its institutions; of which constitutes a dereliction of civic duty inherent in citizenship itself, as citizens are reduced from participants in democracy to spectators of punishment. Meanwhile, the architects and advocates of those principles walk away seemingly untouched, shielded by an ideology that confuses political economy with moral fate.

If this is true, then the question is not merely who failed or who should be punished, but what conceptual frameworks have we subconsciously accepted as immutable—and whether we have mistaken institutional effectiveness for morality. Earlier moral traditions understood political economy not as a system for managing the outcomes of self-interest, but as a domain of judgment—where prosperity without accountability was not success, but warning.

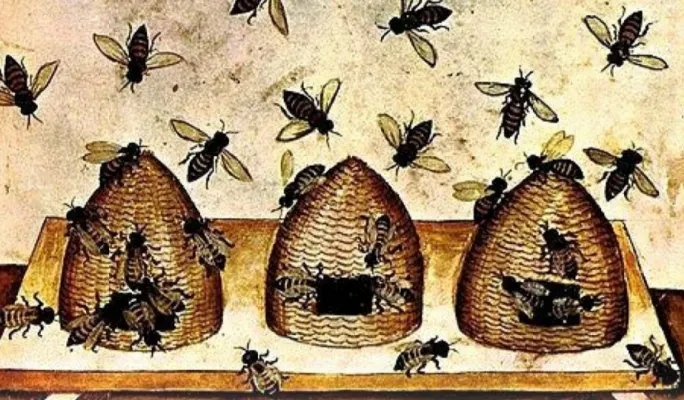

The Fable

More than three centuries ago, Bernard Mandeville captured this contradiction with unsettling clarity in a satirical poem called “The Fable of the Bees or Private Vices, Public Benefits”. It tells the story of a prosperous hive—wealthy, powerful, innovative, and well governed. The hive is also corrupt: its officials bend rules, its professionals exaggerate their worth, its citizens live indulgently and complain constantly. And yet, it thrives. Trade flourishes. Industry grows. The hive is admired and feared.

Still, the bees grumble. They demand honesty. They want a moral society. So the gods grant their wish. Overnight, every bee becomes virtuous.

The result is collapse. Without crime, there is no work for lawyers or judges. Without luxury, artisans lose their trade. Without ambition, commerce slows. The hive empties. What remains is a small cluster of honest bees living in a hollow tree—poor but content, virtuous but diminished. The lesson is cruel and clear: the hive had never been powered by virtue; it had been powered by self-interest.

Mandeville’s point was not that vice is good. It was that societies flourish not because people are virtuous, but because institutions are built to harness self-interest—whether we admit it or not. To pretend otherwise, he warned, is to invite failure and then blame.

The Present

Mandeville did not write the hive as fantasy, but as diagnosis. He was describing a world that was already taking shape—and one we continue to build. Three hundred years later, we live in that hive. We call it laissez-faire.

We build our economy on competition, the profit motive, and Ayn Rand’s philosophy of unfettered individualism—an ideology that, as The Guardian has reported, has been embraced not only by elements of the U.S. political elite, including figures in the Trump White House, but also by powerful leaders in Silicon Valley who treat Rand’s celebration of self-interest as a moral and cultural touchstone. We praise freedom and efficiency. We minimize oversight. We trust markets to police themselves. We accept a certain amount of misconduct as the price of growth.

Then a scandal breaks.

Fraud exposes weak oversight. The illusion cracks, and suddenly the narrative changes. The problem is no longer policy or design, but the virtue or vice of individuals. Welfare itself now becomes suspect, and the question shifts from “How was this governed?” to “Should this exist at all?” Compassion is mocked. Public trust is reframed as gullibility, as if trust were the mistake rather than the absence of accountability. The political and economic elite survive by insisting that failure came from too much kindness—from believing in people at all.

The Elite Double Standard

This is the hypocrisy the Wall Street Journal does not fully confront. Laissez-faire is defended when it shields capital from scrutiny. But when its failures appear in public equity programs, the same philosophy is abandoned in favor of moral outrage.

For the powerful, freedom means flexibility, discretion, leniency, second chances, and deference to complexity (“it’s complicated”), whereas for the vulnerable that same freedom is replaced with surveillance, strict compliance, moral scrutiny, and punishment for error—in essence, zero tolerance.

Risk is privatized upward. Powerful actors are allowed to experiment, fail, and externalize costs. When things go wrong, losses are absorbed by the public. Institutions are protected. Consequences are softened. Risk becomes a privilege of power.

Blame, meanwhile, flows downward. When failure becomes visible, it is attached to individuals or communities, framed as a moral deficiency, and redirected away from those who created the conditions in the first place. The question is no longer “What failed?” but “who can be disciplined?”

The pattern is unmistakable. It works like corporate bailouts in reverse: CEO’s are insulated from consequence while poor unfortunates absorb the cost—except here, institutions preserve themselves by offloading reputational damage onto welfare programs and the political credibility of those who defend them.

The Reckoning

We are not only living through a crisis of moral accountability. We are living through a crisis of truth.

Laissez-faire depends on self-interest but refuses to own it. When consequences surface, accountability is displaced. Until we admit this—until we stop pretending we built a virtuous society rather than an efficient one—we will keep repeating the same story, scandal after scandal, pretending each one is a surprise.