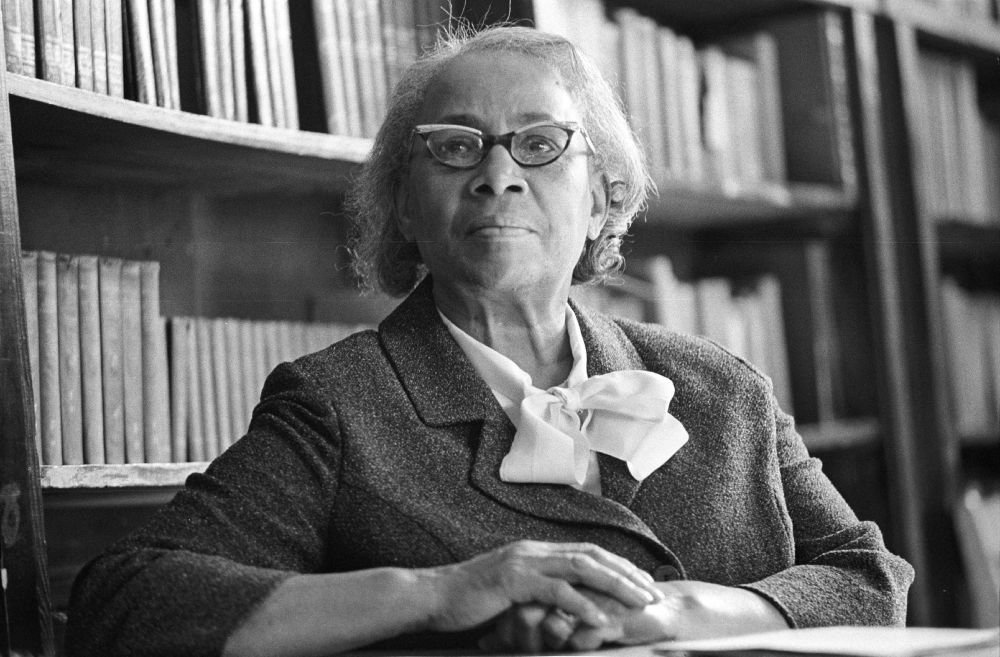

She Understood That Literacy Was Power

Septima Poinsette Clark understood something dangerous for her time: If you could read the law, you could challenge it.

She was born on May 3, 1898, in Charleston, South Carolina, into a world still shaped by slavery’s shadow. Her father had been born enslaved. Her mother, raised in Haiti before returning to the United States, believed fiercely in dignity and discipline. From them, Septima inherited both memory and expectation, the knowledge of what had been endured, and the insistence that more was possible.

As a young girl, she noticed something unsettling. White children in Charleston had access to better schools, better books, better futures. Black children were given scraps, underfunded classrooms, worn materials, and low expectations.

She learned early that inequality was not accidental.

And she decided to become a teacher anyway.

The Classroom as a Front Line

When Charleston refused to hire Black teachers in its public schools, Septima moved to rural Johns Island to teach. There, she saw poverty up close. Many of her students worked in fields before coming to class. Some adults in the community could not read at all, not because they lacked intelligence, but because the system had never intended for them to.

She pursued higher education herself, earning degrees while working full-time. Education was not easy to access for a Black woman in the early 1900s, but Septima refused to let barriers define her.

She also joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

That decision would cost her.

In 1956, South Carolina passed a law forbidding public employees from belonging to civil rights organizations. Septima was asked to leave the NAACP if she wanted to keep her job.

She refused.

After nearly four decades as a teacher, she was fired. She lost her pension. Her security. The career she had built.

But what the state did not realize was that it had just removed her from a single classroom and freed her to build thousands more.

Teaching Democracy

Septima Clark began working with the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, a training center for social justice activism. There she helped develop what would become one of the most quietly revolutionary programs of the civil rights movement: Citizenship schools.

The concept was simple. Teach Black adults how to read, write, and understand the Constitution.

But in the Jim Crow South, that simplicity was radical.

Literacy tests were used to prevent Black citizens from registering to vote. The tests were deliberately confusing, inconsistently graded, and often impossible to pass, even for educated people. They were not designed to measure ability. They were designed to maintain control.

Septima saw through it.

If people could read the form, understand the questions, and write confidently, the system’s disguise would crack.

So she trained teachers. Those teachers trained others. Classes were held in churches, community centers, and living rooms. Lessons included reading newspapers, filling out voter registration forms, and understanding local government.

But more than literacy, the schools taught something else: Confidence.

By the early 1960s, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) adopted the citizenship school program, and Septima Clark became its director of education. Under her leadership, the program spread across the South. Tens of thousands, eventually hundreds of thousands, of Black citizens registered to vote.

She did not lead marches. She built voters.

The Movement Within the Movement

Even as her influence grew, Septima faced resistance – not just from white officials, but sometimes from within the movement itself. Male leaders did not always welcome women into positions of strategic leadership. Her work was sometimes dismissed as secondary.

Yet Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. defended her, recognizing that the movement needed more than speeches. It needed infrastructure. It needed people prepared to participate in democracy the moment the doors opened.

Septima Clark provided that preparation.

She believed ordinary people, when given the tools, could govern themselves. That belief reshaped the South.

Her Legacy, Reclaimed

Septima retired from the SCLC in 1970, but she never stopped advocating for education and civic participation. She eventually regained her pension. She served on the Charleston County School Board. She received national recognition later in life, including honors from President Jimmy Carter.

But her true legacy was never a medal. It was the quiet multiplication of voices. Every person who registered to vote because they finally understood the process, that was her work.

Every ballot cast by someone once told they were incapable, that was her legacy.

Septima Poinsette Clark died in 1987.

History often remembers the marches. The speeches. The arrests. But before people could march, they had to believe they mattered. Before they could vote, they had to know how. Septima Clark taught them both.

And in doing so, she proved that sometimes the most powerful revolutions begin not in the streets, but at a desk, with a pencil, and the decision to learn.