In 1890, while living the life of a luxurious and infamous playwright, Oscar Wilde compiled all his imaginatives on hedonism, temptation, and human nature into a blood-driven, sex-filled young man he most definitely saw himself in, Dorian Gray.

“The Picture of Dorian Gray” remains Wilde’s only novel, first published in a monthly magazine. Wilde wrote a few versions of the story, censored and edited by his publishers, but an artists’ work is always a reflection of the artist, and Dorian Gray, while wordy and sometimes difficult to follow, provides a wider scope for hedonism and victorian-era life.

Prestwick House

The cover of Prestwick House Literary Touchstone Classics edition; shows the marred portrait of a once beautiful Dorian Gray.

But the thing I remember most about Dorian Gray is complaining about it more than reading it. Wilde, who wrote mostly essays and dialogues apart from plays, explored three different personalities within himself and had lyrical debates amongst them. To him, this story was a philosophical fiction of himself.

In an 1894 letter, Wilde wrote, “[“The Picture of Dorian Gray”] contains much of me in it – Basil Hallward is what I think I am; Lord Henry, what the world thinks of me; Dorian is what I would like to be – in other ages, perhaps.”

I was grateful to discover nearly 30 different versions of the story made for the screen, which combines my love of literature and film-industry knowledge nearly as beautifully as Dorian Gray supposedly is. Some took it as a short philosophical play, or a drama-room comedy, but most understood the story to be horror, full of gore, and a reflection on the evilness of human nature.

Now I did read the book, and I have dissected my Union Square edition apart. Wilde’s own sentences can last more than a typical paragraph, with hypothetical situations, complexities, theories, and proposed outcomes all taking place within one breath.

An ode to the ones attempting to nail down a precise belief system of the characters as their actions and dialogue are riddled with inconsistencies and conflicts. But perhaps that was an attempt on Wilde’s part to illuminate the inconsistent nature of humans and their beliefs – or to be as controversial as he could be.

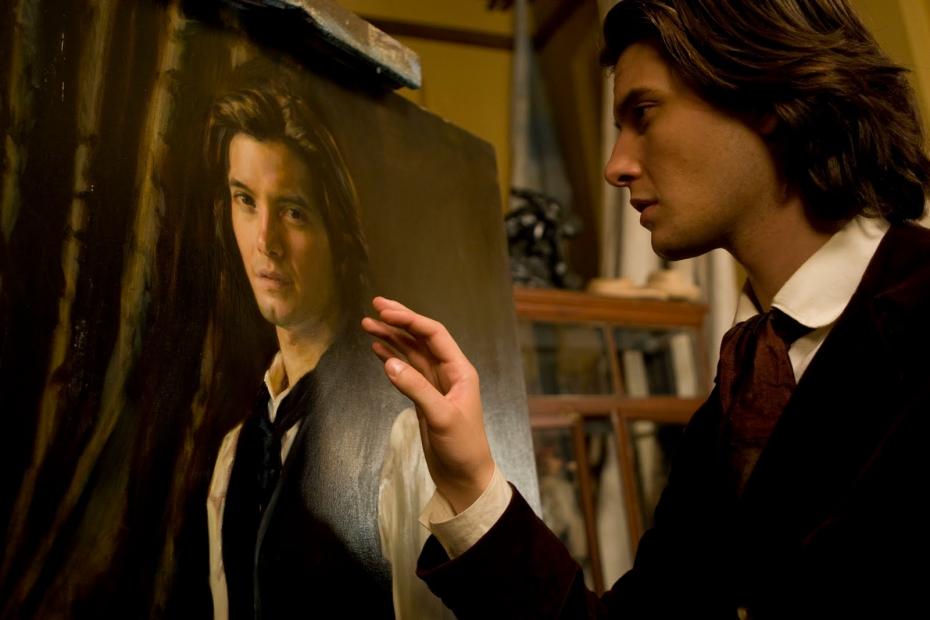

I would recommend the novel to students of philosophy, horror fans, and an intermediate enemy. To everyone, I’d recommend the 2009 make of the movie, titled “Dorian Gray”, starring Ben Barnes as Dorian Gray and Colin Firth as Lord Henry ‘Harry’ Wotton. As the spooky season approaches, and we look for new scary films to curl up with friends, this would be perfect.

The gritty Victorian aesthetic, haunting audio, and gory scenes make it perfect for appropriate audiences to have a good discussion over. Ben Barnes, forever a master at bringing literary characters to life, and Colin Firth, a charismatic businessman who can make us believe everything he’s telling us, fall into it together.

Dorian Gray began as an empty canvas – a handsome and wealthy gentleman of 20 takes over his late grandfather’s estate in the heart of Victorian-era London. This was a time in Britain where the world was expanding, and the Crown held the status of the most powerful empire in the world. And Dorian, a bachelor with the world at his feet, has his entire life to explore.

Upon returning to London, Dorian reunites with an old acquaintance, Basil Howard, a deeply moral and fearful artist who begs Dorian to sit for a portrait. Dorian agrees, and the artist becomes enamored by his subject.

“What the invention of oil-painting was to the venetians, the face of Antinous was to late Greek sculpture, and the face of Dorian Gray will someday be to me,” says Basil about his muse.

Napoleon Sarony

A photograph of young Oscar Wilde taken in 1882.

Now, had these two been written in 21st century literature, their interactions may have gone a bit spicier. In fact, in 2001, an ‘uncensored’ version of the novella would be published with roughly 500 words of original text restored to the story, as the passages were removed without Wilde’s knowledge in the original publication.

But as Basil represents morality, good, and conservatism (not in a political sense), his dear frenemy Lord Henry ‘Harry’ Wotton represents the opposite.

The joy in writing, for some authors, is the ability to create absolutely fake characters that have no basis in reality, but simply serve a purpose for the author’s main character. We can’t have a story where the main character remains the same throughout – we read to experience the changes they go through for ourselves.

So if you are wanting to indulge in every temptation, seek out forbidden pleasures, and all around try your hand at being evil, Dorian’s journey with Harry might be enticing enough to lead you through the story Wilde put out for us.

But what leads Dorian down the hedonistic path of sensual, physical, and mental experimentation? How does a seemingly perfect man turn into a demon against nature and good? A deal with the devil, of course. One that ensures Dorian remains pure despite acting against all purity.

As Wilde put it, “What the worm was to the corpse, his sins would be to the painted image on the canvas. They would mar its beauty and eat away its grace. They would defile it and make it shameful. And yet the thing would still live on. It would be always alive.”

And so would Dorian, for the decades the story covers. Dorian travels to the darkest corners of the world and of consciousness to seek out the most devilish temptations while he can. And if every act of evil, every hint of age, skipped over you and onto the painted image instead, how marred would ours become?

“The books that the world calls immoral are books that show the world its own shame,” Harry says.

It’s interesting prose, to be sure. I imagine passages taught in English classes that delve into debates on human nature, goodness and the devil, and though-provoking conversations on the topics. But as this story provided enough conflict, Wilde’s own life provided the controversy. But that is an article for another time.