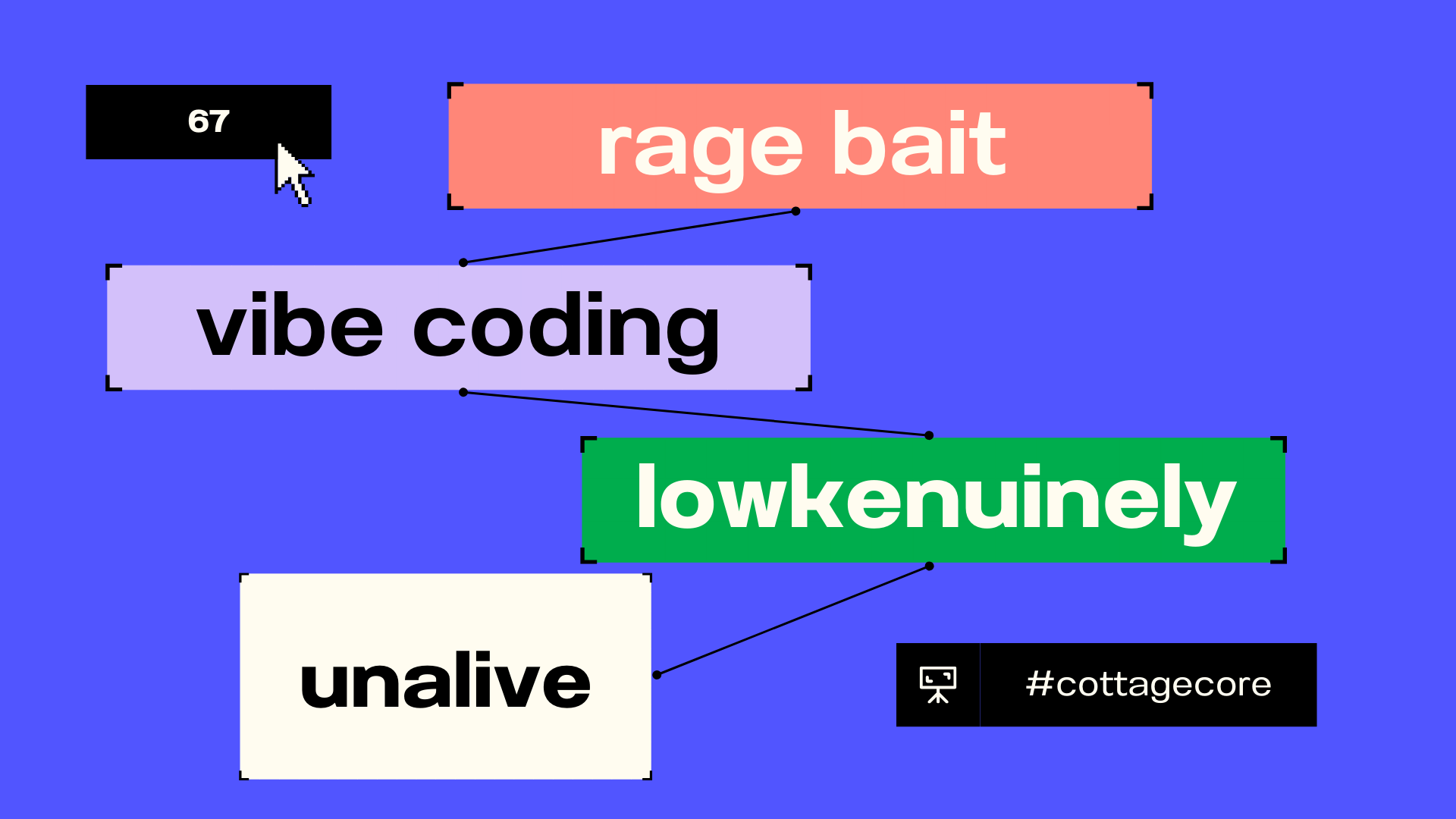

“Rage bait,” “67,” and “vibe coding” all have something in common: They were named Word of the Year by various dictionaries. Another thing they have in common: They are terms that have been pushed by social media algorithms that have made their way to common usage.

Social media has a big influence on our language. The way many people talk online is often different from the language used during in-person interactions – at least that used to be true most of the time. Recently, the language and slang used on social media has seeped into real life conversations more than ever before.

In daily interactions amongst younger people, it would be strange if someone didn’t make “67” jokes while making the hand gesture associated with the phrase.

Social media influencer Adam Aleksic (known as “The Etymology Nerd” on social media) focuses on how social media algorithms are influencing how language is evolving and playing a massive role in etymology as we know it in the modern day. He even wrote a book called, “Algospeak” that dives into specific examples, including a song that went viral last summer about “sticking out your gyat for the Rizzler.”

In a TED Talk that is a companion to his book, Aleksic discusses how while language has always been viral in nature, “reproducing and changing as they infect different people along social networks,” social media has accelerated this process. Seemingly obscure words can start as niche inside jokes from an in-group and quickly turn into common vernacular not just online but in social interactions and even academic settings.

Sometimes words spread on social media due to censorship, such as the rise in popularity of the word “unalive” as opposed to “kill” that grew popular due to TikTok’s censorship of content with the word “kill.” In a survey conducted by Aleksic amongst middle-school teachers, the word “unalive” has even appeared in student essays such as one that discusses “Hamlet’s contemplation of unaliving himself.”

Social media doesn’t just control etymology via censorship. Social media also creates an environment where labels such as “cottagecore” are deemed as “trendy metadata” that can be used by companies to generate profit from social media users.

Let’s say that someone looks at content that uses the label “cottagecore” and enjoys what they see. The “cottagecore” aesthetic then becomes part of that person’s identity to some degree, and every time that person gets “cottagecore” content, they feel seen and might even want to purchase clothing or decor that aligns with this aesthetic.

While this might seem harmless, it is important to note that terms and identities like “cottagecore” were created and pushed because the business model of social media platforms are based on repetition, neat labels, and users looking at content continuously in order to make money.

Furthermore, the label “cottagecore” is merely a tame example of some of the trendy labels across social media. A surprising amount of the trendy words spread by social media come from incel ideology. This is shocking considering that the incel community is known to be dangerous and misogynistic. For instance, the Rizzler song that was mentioned previously also contains the lyric, “I just want to be your sigma.” The term “sigma” started as a word incels “[used] to describe their desired position outside of the social hierarchy,” according to Aleksic.

Most people who use words like “sigma” likely don’t have any idea that the word has such an association. This speaks to the common occurrence of social media controlling our lives in ways that we don’t even realize, even if it is happening right in front of our eyes.

This isn’t all to say that we can’t enjoy the humor that comes with online vernacular. Laughing at memes can be a way to create community and build connection, but it is also important to note that all memes start somewhere, and knowing this origin can make social media users more informed on their choice of words and the weight that they hold. Being informed is “lowkenuinely” the best way to understand our ever-changing language in the age of social media.