Over 30 years after his gruesome serial murders, controversial media portrayals of Jeffrey Dahmer continue to intrigue and disturb viewers.

This review will compare the factual fidelity and ethical problems found between two biopics, “My Friend Dahmer” and “Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story”, versus the documentary series “Conversations with a Killer: The Jeffrey Dahmer Tapes”.

Netflix

The documentary series “Conversations with a Killer: The Jeffrey Dahmer Tapes” was created in 2022.

While dramatizations aim to build empathetic backstories of killers like Dahmer, they often stray from truth and glorify the perpetrator. Meanwhile non-fictional accounts, for all their grisly details, bring an honesty about society’s failures regarding these criminals. Across formats, representing Dahmer reveals our unresolved feelings of horror and guilt tied to his unchecked killing spree.

The most striking contrast between these works lies in faithfulness to the facts. Of the three, “Conversations with a Killer” (2022, directed by Joe Berlinger) hews closest to known details of Dahmer’s murders, aided by direct archival footage of Dahmer recounting his crimes. As a documentary, verifiable truth takes priority over artistic license.

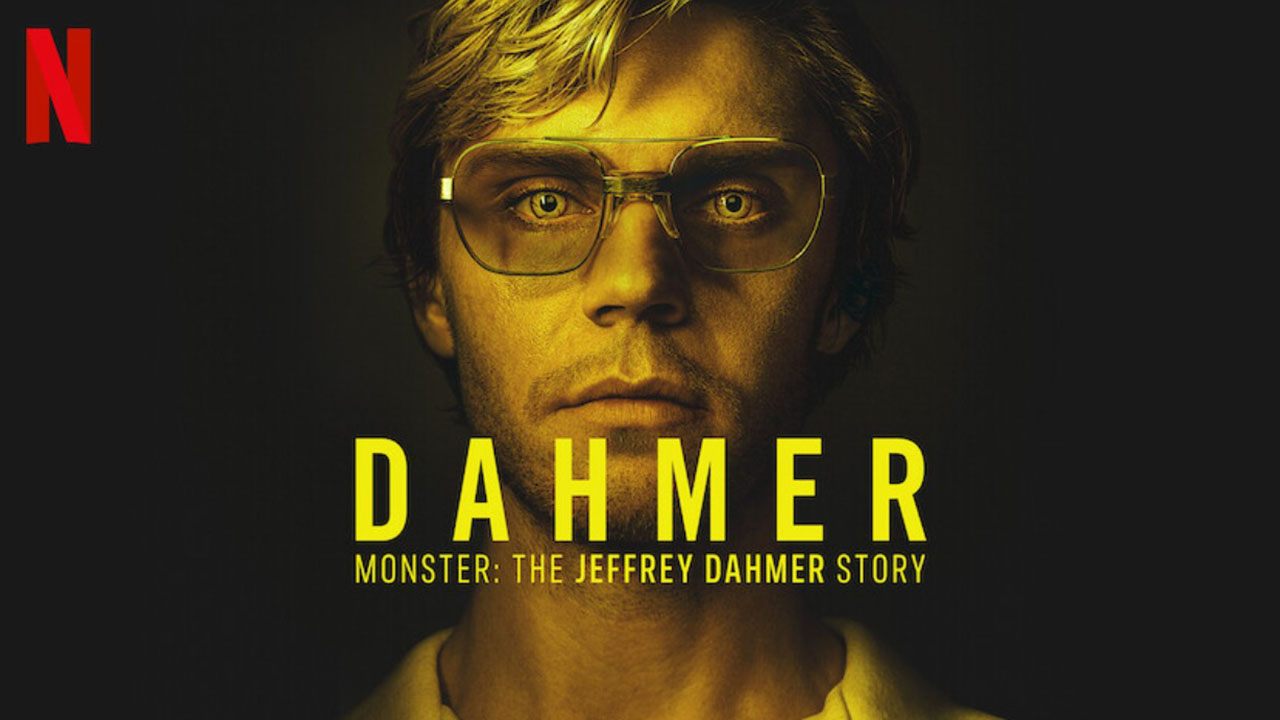

“Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story” (created by Ryan Murphy) takes liberties by conjecturing private scenes with victims, such as Tony Hughes. While dramatizations cannot completely avoid fiction, “Monster’s” liberties seem ethically questionable for ongoing cases.

“My Friend Dahmer” (2017, directed by Marc Meyers) blends fact and fiction by adopting the memoir perspective of Dahmer’s high school friend. While this viewpoint naturally limits available details, Derf was present for many disturbing moments of Dahmer’s early urges.

The film does slightly embellish events but bases scenes on Derf’s remembered experiences. Of the biopics, its fidelity and firsthand knowledge make “My Friend Dahmer” the most accurate depiction of Dahmer’s psychology and youth. Still, none can match the documentary’s factual reliability regarding the killings themselves.

Just as truthfulness varies across works, so does the centrality of Dahmer’s victims. “Monster” takes care to name all 17 victims and give backstories to several, better humanizing them than the other works. “Conversations” feature victim family members discussing their enduring pain and senselessness of the murders. However, both focus more screen time on Dahmer himself than those he killed.

FilmRise

“My Friend Dahmer” blends fact and fiction in a dramatic biopic.

“My Friend Dahmer” problematically omits Dahmer’s victims entirely. Its timeline ends before the murders, but additional context or details on lives lost could have created a sobering contrast to Dahmer’s high school antics. As the most unethical of the works for overlooking those harmed by its subject’s future actions, “My Friend Dahmer” reads as regretfully glib rather than a piercing psychological portrait.

Any work portraying real murder cases risks romanticizing horrific acts if not handled responsibly. “Conversations” largely avoid glorification through blunt facts and emotional interviews—it is difficult to empathize with Dahmer’s actions despite gaining insight into his psychosis.

“Monster” somewhat humanizes Dahmer excessively in dramatizing his life and internal thoughts, taking problematic liberties. Yet its bold indictment of systemic failures around Dahmer counterbalances this with messages of accountability and prevention.

Of the three, “My Friend Dahmer” feels most ethically questionable—its charismatic performance of a pre-killer Dahmer elicits occasional laughs for shock value. Without addressing future impact or victims, its sole message comes across as kids can grow up to be monsters.

Though factually grounded, its narrow sight makes the film land more as a lurid stunt than social commentary. Perhaps no work can fully encapsulate the ongoing trauma caused by Dahmer’s crimes, but “Monster” and “Conversations” at least minimize dangerous indulgences.

Ultimately, the documentary format with direct testimony proves most responsible for portraying Dahmer’s disturbing case. While dramatic works have stronger emotional impact, bending truth can skew empathy toward violent offenders over victims. True crime should enlighten audiences on societal problems that enable these criminals, not just offer lurid entertainment.

However, even respectful documentaries can cause more trauma. Recent semi-fictionalized works like “Monster” have brought criticism from victims’ families, who felt revictimized and exploited by the show’s heavy artistic liberties.

As one of Dahmer’s victim’s cousins expressed, “It’s retraumatizing over and over again, and for what? How many movies or documentaries or whatever do we need?” Their insights reveal issues around informed consent and privacy even nonfiction works contend with when reconstructing crimes.

“Conversations” maintain that delicate balance best with transparency, honesty, and dwelling on loss of life—the cost of normalizing predators like Dahmer remains far too high even decades later. Yet no single work captures the full picture; complex human realities exceed even ethical true crime.

The greatest justice comes not through criticism but affirming the dignity and humanity of those affected by turning their stories into lessons for preventing future violence. That moral duty persists long after the cameras turn off.